“Capital Deepening” and Artificial Intelligence at Labor’s ERR

Discussion for activists – red, green and purple (part 2)

Canadian labour economist Jim Stanford’s new report for union and other activists about the productivity issues at stake in the government’s Economic Reform Roundtable (ERR) claims Australia’s productivity problem is not so alarming. He shows how flawed productivity measurements can be, as pushed by mainstream economists, including Labor politicians. He also reaffirms how wages paid lag well behind labour productivity performance.

Well, if labour productivity is not a serious problem, what is?

The clues lie in some new jargon: “capital deepening” (CD), the ratio of physical capital (machinery, factories, tools) to workers or labour hours, and its connections to profits, competition (between firms and nations) and artificial intelligence (AI).

This jargon obscures Labor’s use of remote and elitist consultation, like the ERR, to guide its management of general economic fragility, climate disaster and war-posturing. Consequent reform will be done to workers, their communities and the natural environment on which they rely, cultivating a dull acceptance that the issues are just too complicated.

“CD” and its association with AI is a phrase hiding more than it reveals.

From the point of view of employers, the profit connection is critical. From the point of view of working people and the environment, new investment in climate change reversal and the rescue of nature is essential, even while capitalism reigns.

Instead of deciding that investment is not our business, we must pursue wider, deeper discussion in the working-class majority about how dangerously it can work and how it connects to our daily lives and our futures.

CD in plain language

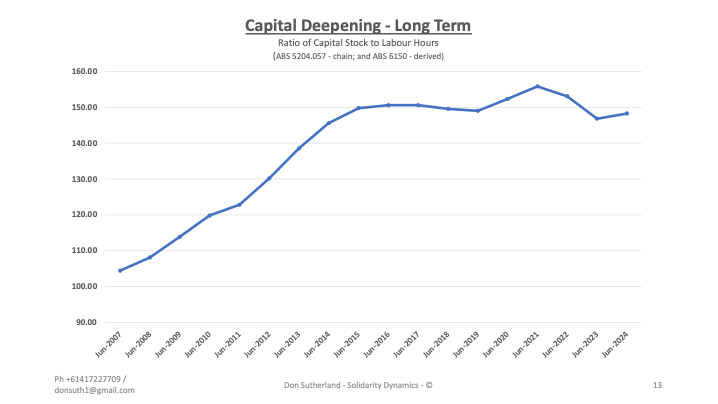

CD measures fixed assets – physical equipment, machinery and tools, factories, warehouses, depots, etc - relative to labour input, the number of workers, or working hours, required to bring them to life. Mainstream economists call it the “capital-labour ratio”.

Workers know firsthand how outdated tools hinder output, both quantity and quality, yet the investment decisions remain controlled by employers. For many, the inadequacy of the equipment they use is often the bane of their working lives.

For workers, CD isn’t abstract: it dictates workplace safety, bargaining power, and job precarity. Corporate-controlled investment decisions—driven by competition—ignore social and ecological needs. Unions and communities must invade this terrain.

CD means raising the capital stock – the quantity of fixed assets – relative to the number of workers using it or their working hours required to operate it.

The AI Connection

AI is a form of CD. In essence, it is hardware originating in natural resources and depends on workers’ intelligence and effort, energy and water. Its expansion demands data centres, chips, and infrastructure, thus deepening capital stock. While AI could aid climate action, its private control relies on worker exploitation (job losses, speed-ups, deskilling) and environmental harm.

CD is shaped by millions of employer controlled investment decisions that impact on workers’ daily lives and those of their families: the quality and safety of equipment and the workplace, the pace of work, whether one has a job or not and, if so, how precarious it might be, bargaining power for wages and conditions, the need and opportunity to use all skills and knowledge held by the worker and to get new levels, how much of what Nature provides, and the nature and volume of the waste that is pumped out of the production and distribution processes.

The employers’ decisions to purchase and accumulate the capital stock are a very big deal for workers and their communities. Not understanding how it works weakens working-class life and the actions we develop to make those lives better, including the defence and rescue of the environment. The investment decision should be defined as union business, as community business, not left to the boardroom.

The extra element of the investment decision is competition. The structure and intensity of competition between firms, no matter how big and dominant they are, is not absolutely under their control. Competition demands that companies, for their continuity, invest to exploit for a profit that is equal to or better than their competitors. The competition dynamic is reproduced between nation states, as we see right now, for example, between the USA and China, and the emergence of the BRICS.

Understanding CD and other aspects of investment strengthens union and environmental claims on employers and governments for socially useful new investment and enables a more profound grasp of how society works.

Why is CD being made an issue? The evidence?

CD estimates and the associated rate of new physical investment can be calculated using Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data in its annual National Accounts (not the quarterly version).

Notwithstanding the problems with this data, as described by Jim Stanford and others, we can use it to improve our understanding of what is happening at the industry and national level because of boardroom decision-making and government policy.

Corporate Australia’s Capital Deepening Performance is poor

Put simply, the private sector employers, often referred to as the “market sector”, have not been investing enough. They have failed both people and Nature, and past governments have permitted that failure. The Labor government wants a “market-led” solution, thus maintaining the dynamic and the boardroom controls that have produced the problem.

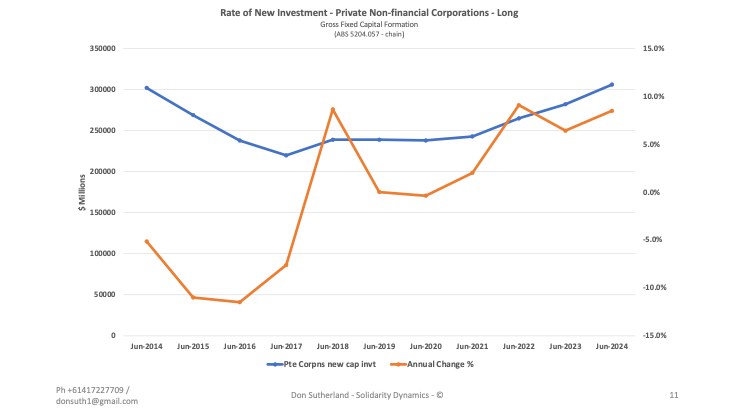

The rate of new physical investment

The rate of investment is the value of new investment in a period relative to the profits taken. The new investment adds to the existing capital stock that is available to workers in the daily labour process.

The primary source of productive investment is how much business owners (and/or their Boards) take out of their profits to purchase new fixed assets. (Tax breaks, public loans, bank borrowings and publicly funded subsidies are also important sources of investment, in turn dependent on taxation policy. For now, that is a separate discussion.)

Investment in new or upgraded fixed assets is just one of several options for capitalists (private owners, stock exchange owners and their boards). The others include how much to add to personal incomes of owners and key executives, interest paid on loans, how much to “trade” on the stock exchange (e.g. share buybacks) or the money markets, how much to “save” or move offshore, e.g. to a low-wage haven, and how much might be needed to reduce or dodge taxation.

Private sector physical investment has stagnated.

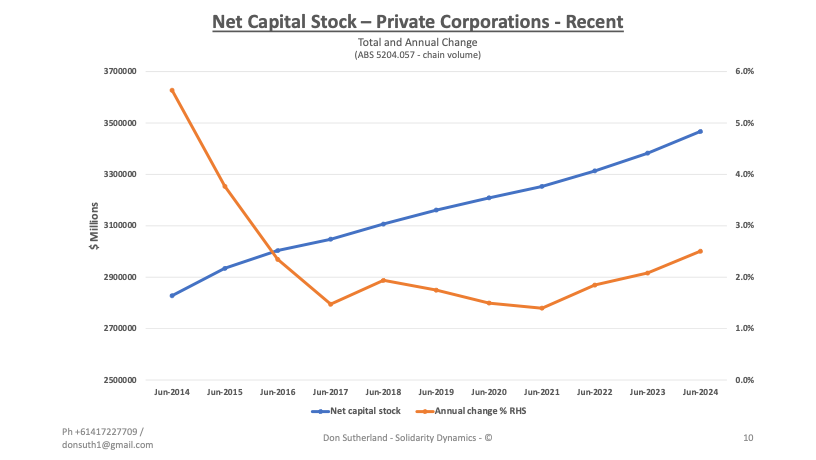

We see net capital stock (after depreciation) growing, but at a slower rate. The focus is on private non-financial corporations because they are the biggest and most influential sector.

The next graph helps to explain why, showing the rate of new investment, that is “gross fixed capital formation” (GFCF), from profits taken by those corporations. We see over 10 years a long flat period ending with an upward tick. (More recent quarterly data shows it falling again.)

The result is the CD problem that the Treasurer, his Productivity Commission, and other mainstream economists talk about to justify AI investment.

Weak CD that predates the pandemic by about 7 years. Jim Stanford‘s paper shows much the same thing, referencing back to the 1960s.

Connecting CD to profits and wages

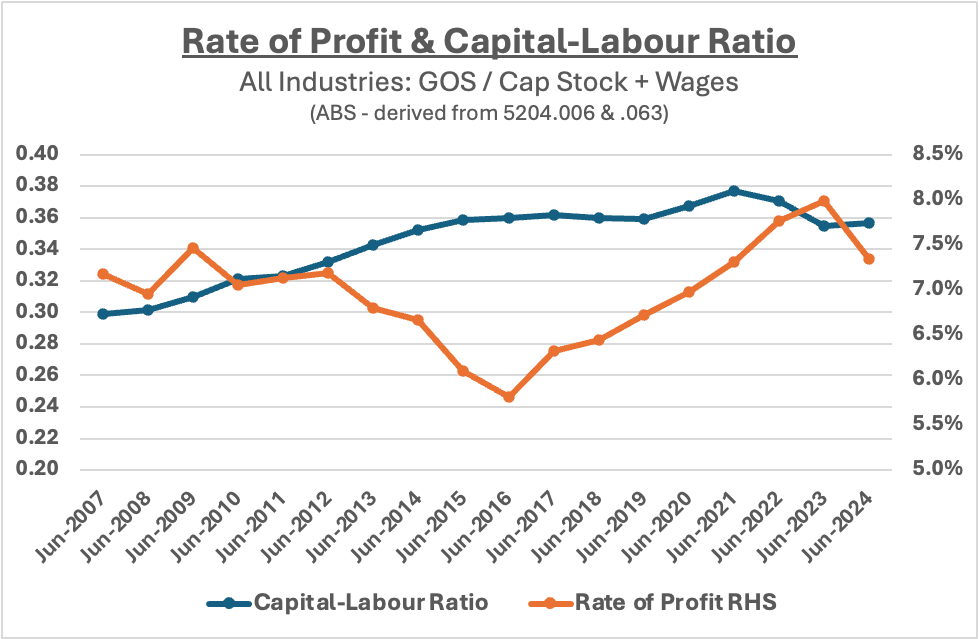

Profitability relative to competitors is the primary drive for every employer. Where does CD fit in the drive for profitability?

Our starting point was established in the previous post; briefly, productivity and profitability are not the same, but they are bound together within hours worked, when workers bring the fixed assets to life.

Put simply: PROFITABILITY = TOTAL PROFITS RELATIVE TO THE SUM OF CAPITAL STOCK + WAGES.

Thus, we see a startling contradiction: CD initially reduces profitability, and from time to time, as a trend, the opposite of what is required.

That might be resolved by increasing prices of consumer goods, including gouging, and/or downward pressure on wages. The latter explains why employer organisations oppose wage increases and improved workers’ bargaining rights, especially the right to strike and why raising union density and combativity is essential for workers and their unions.

Here is a very cautious snapshot, using ABS data, of what has been happening, indicating the real problems the employers (and a sympathetic government) want to solve, if necessary, at the expense of more severe exploitation of workers and the environment.

We see a general trend: while the capital-labour ratio grows, there is downward pressure on profitability. Profitability is the real problem, productivity is its proxy.

Workers’ and Community Alternatives: “Socially Useful Investment”

Let’s be clear, highlighting the profit problem does not require the workers’ and environmental movements to rescue profits to win their programme.

Investment decisions, workers’ rights and communities

Corporate-controlled CD and associated AI harm workers and the environment. It determines job security to defeat competitors or survive a new generation of technology; it might destroy the most profound rock art, make climate change even worse, and continue habitat and species loss.

As important as the investment decision is for daily life, workers and communities have either no or at best tightly constricted statutory rights to challenge or change or negotiate over an investment decision, including the general prohibitions on industrial action. Environmental activist organisations are more focused on disrupting investment decisions than modern unionism. Each movement needs the other to learn from each other.

Winning “in advance” notification and negotiating rights will depend, as always, on escalated and ever-widening worker and community education, coupled with breakout struggles and confrontations whenever these happen. Personal and collective understanding of how CD and AI affect people and the environment will rely on, and at the same time, improve the effectiveness of their unionism. Good examples are emerging that provide clues of a more widespread struggle.

The urgent and democratic “just transition” to slow and reverse climate change must include worker and community capacity to control and direct new technologies. History shows good examples, like the NSW builders’ labourers’ green bans and the Lucas Aerospace workers’ intervention.

The critical elements of the alternative should include more recreation time with no loss of pay, 2-3 hours of paid vocational education leave per week, new minimum workers’ rights to consultation and negotiation before an employers’ investment decision is made, including “ethical” AI transparency in algorithms (no secret black-box corporate AI), the genuine right to strike in multi-employer bargaining, no forced layoffs, public ownership with democratic control, and socially useful investment criteria.

Democratic public ownership is essential to direct and set standards for medium and long-term socially useful development and propel the possibilities of a better society. That might focus on publicly owned data centres, renewable energy, public housing and public transport manufacturing.

(Note: the taxation and foreign investment linkages to all of this will be discussed separately.)

The tendency is for the rate of profit per commodity sold to decline. That is because productivity increases for it is measured as 'output per hour of labour'. More commodified goods and services are produced per hour of labour using technologically advanced machinery, which includes Artificial Intelligence (AI). It should be remembered that labour produces AI, it just doesn't own it.

As the rate of profit declines for producing goods and services for sale, the market share for the capitalist seller must expand. If it can't expand or if sales bring lower profits than those which can be had through speculative investments like Crypto will increase. Another avenue is to invest those profits into areas of commodified wealth where supply is less than demand, like real estate, where prices are inflated, mostly because of political decisions made by the people who are elected to make laws. It should never be forgotten that the people elected to govern come almost exclusively from the upper 10%, the bourgeois who own most of the corporate stock and real estate.

On the matter of wages, it is a fact the lower wages translate into higher rates of profit, not lower prices for the goods and services sold in the marketplace of commodities. Last I heard, real average wages in Australia are at the level they were back in 2011.